Quality in Finance

How to integrate Quality thinking into a business’s finance department through better budgeting practices, balance sheet management, and performance measurements.

Thoughts on Quality

This series will consist of practical applications of Quality, as defined in Thoughts on Quality. Each article will begin with this brief summary to calibrate the reader’s understanding of the term. If the reader feels sufficiently calibrated, they should feel free to skip to the next section. In that work, a definition of Quality is arrived at that is both distinct from current industry thinking and from how the term has been defined by the quality gurus of the past. This definition is:

Quality /kwŏl′ĭ-tē/ noun

Profit measured over an eternal time horizon and considering all externalities.

The maximization of human prosperity.

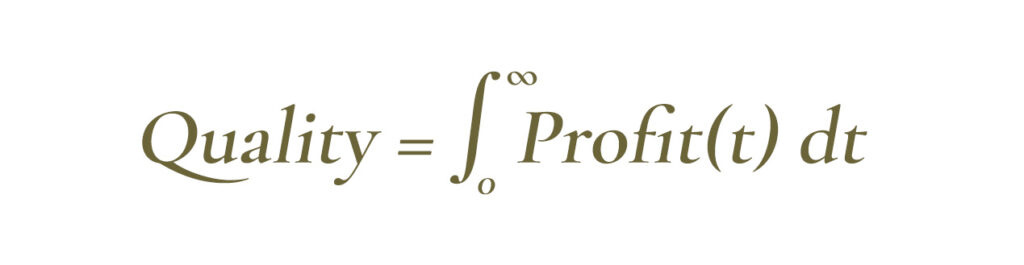

For those mathematically inclined, this basic formula can be extrapolated to help conceptualize it:

Graphically, this makes Quality the area under the profit curve. Read Quality is Integral to Profit for a more comprehensive breakdown, including how to consider externalities and opportunity costs.

Zero-Based Budgeting

Quality in a business starts with proper allocation of capital. To ensure a maximization of profit in the long-term, capital should be allocated with consideration for all opportunity costs and must not be destroyed through malinvestment. Businesses are living organisms in an ever-changing environment, and as such, proper capital allocation cannot be stagnant. Capital allocation must adapt to these changes or malinvestment is a likely outcome. Businesses typically review and determine how best to allocate capital annually during their budgeting process. As a brief note before getting to the main point, this structure is adopted for efficiency, but Quality ideas should never be rejected because they are “not within the budget.”

Traditional budgeting methods rely on the previous year’s budget as a baseline and adjust as needed. There is an implicit assumption with this methodology that things were correct in the first place. Therefore, it is considered efficient to leverage work that has already been completed. This assumption should be challenged on principle, but businesses will often utilize this method even in times of crisis. For example, even if there is a changeover in the management team (i.e., the creators of the budget), which would imply something was wrong with their decision-making capabilities, the budgeting process will still default to the previous year as a baseline. This type of budgeting encourages a creeping expansion of spending, discourages change, and disincentives the creative destruction that is required for continued prosperity.

After years of autonomous growth in spending, the business will inevitably be confronted with an inability to grow revenue. The response is typically to cut costs to improve profitability. These cost-cutting efforts are often temporary solutions focused on short-term profitability. They focus on things like cost-of-goods-sold (COGS) that often have the consequence of a reduction in product quality. This is not to say that a reduction of COGS is always an anti-Quality activity. Occasionally, right-sizing staff is required for operational efficiency and sourcing more economic materials is required for design excellence, but frequently there is equivalent (or greater) savings to be found in discretionary spending areas that would not just avoid a reduction of Quality but perhaps even improve it.

A business can avoid this cyclical inevitability by adopting the methodology of zero-based budgeting (ZBB). By contrast, ZBB is a budgeting methodology that encourages change and creative destruction. The concept of ZBB is in the name. The business starts from an assumption of zero expenditures and is required to justify every dollar in their budget, as if it were new. This process removes the momentum of budget growth, leading to increased profit. ZBB encourages managers to reduce costs by searching for productivity gains and highlights potential malinvestment. In addition, it increases transparency and accountability. It improves profitability in a thoughtful and sustainable way, which improves Quality.

Defaulting to the expedience of traditional budgeting methods may have made sense when the economy was more stable and the pace of disruption was slower and more predictable, but we are an age of technological innovation that frequently makes defaulting to plans developed for last year’s environment unreliable. The perceived efficiencies of this methodology are lost in the final analysis when accounting for the opportunity cost of non-Quality spending. If businesses want to ensure that they are making Quality decisions year-after-year, they should dispense with the traditional budgeting methods (and their perceived efficiencies) and adopt ZBB.

De-financialization

Quality in a business might start with capital allocation, but it ends with its balance sheet. Long-term profitability, achieved through Quality decision-making, should result in an accumulation of assets (or capital) and a strong balance sheet. At least, this is what should be expected for a business in the real economy. Unfortunately, businesses are forced to operate in an abstract economy1, which is best characterized as one that utilizes an inflationary monetary system as its unit of account (UoA). In an abstract economy, balance sheets are an afterthought and large cash positions are considered a liability. This is made most apparent from the metrics we use to determine a business’s value, which are often a measure of short-term cash flow, completely agnostic to the strength (or lack thereof) of the business’s balance sheet. The use of these metrics and the emphasis on short-term thinking is incentivized by the existence of inflation.

Inflation makes holding cash on your balance sheet (or saving) akin to holding a melting ice cube. It is thought of as a liability because it is one. Saving provides a business the flexibility to take advantage of opportunities that are not immediately actionable. It makes businesses more robust and resilient to market downturns, which may arise from simple supply-demand shifts or for macroeconomic reasons out of the business’s control (or ability to prepare for). If a business could save, it would have the effect of lengthening its time preference, but saving is irrational when cash balances must be accumulated in an inflationary currency.

Most businesses, cognizant that their country’s currency is inflationary, stock their treasury with things like United States Treasury bills (T-bills), certificates of deposit (CDs), money market funds, or high-grade corporate debt or bonds instead. In short, assets that are liquid and low risk, but provide some yield so as to overcome the effects of inflation. The problem with this approach is the following: interest rates of these low-risk assets are heavily influenced by the Federal Reserve federal funds rate, which is one of the levers used to offset inflation. This lever, however, is based on the government established measurements for inflation, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the Producer Price Index (PPI). These measurements are low-resolution, often not accounting for a reduction in product quality, and have many technical flaws, the most obvious being that “core CPI/PPI” exclude food and energy2. These government manipulated measurements all understate the true rate of inflation, which can be pragmatically defined as the decrease in purchasing power of the currency being utilized. As such, current treasury strategies are simply accepting a destruction of capital, a somewhat slower destruction than simply holding the currency, but a destruction none-the-less.

In an inflationary environment, with savings off the table, businesses are forced to either invest the capital quickly (and agnostic to market opportunities), which makes a business prone to malinvestment. For many reasons, this (mal)investment frequently takes the form of mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The pressure to realize short-term returns incentivizes the business to invest in something that is already productive, rather than attempting to innovate and create something that doesn’t already exist. From a Quality perspective, M&A is basically a neutral activity, not accounting for the costs associated with the activity itself. If the integration is well planned and executed and the two businesses have synergies that generate Quality, it can overcome the costs of M&A but being pressured into the investment as a method of avoiding the effects of inflation significantly increases the likelihood of it being an anti-Quality activity. If this, or any other type of malinvestment, can be avoided, the only remaining alternative is for the business to be pushed into a hyper-financialization cycle. Increasing the likelihood of malinvestment is an obvious anti-Quality force, but a hyper-financialization cycle is perhaps even more so.

Decapitalization (or returning profit to shareholders) is the first step in the hyper-financialization cycle. Common mechanisms for this are things like stock buybacks or dividends, but regardless of the mechanism, the result is the same, a weakened balance sheet. Decapitalization is akin to consumption, and it has the inverse impact on a business as does saving. It makes a business inflexible and reduces their ability to take advantage of market opportunities. It makes them less robust and more susceptible to market downturns. A well-capitalized business can withstand many years of unprofitability without existential threat, but a decapitalized business risks bankruptcy at any given downturn in the market.

Once decapitalized, if a business has a Quality idea (i.e., one that can grow their business), they are either forced to take out loans or sell equity. This is the next step in the hyper-financialization cycle. Typically, businesses are hesitant to dilute their shareholders, so they decide to leverage their existing business operations. The interest payment associated with these loans have a direct impact on profit, but the loan repayment terms also create an anti-Quality environment with incentives for short-term decision-making. For example, if a Quality idea requires eleven years to fully realize, but the loan acquired to implement that idea has a ten-year repayment term, it creates pressure on the business to execute within the shorter timeframe. Leverage is not inherently an anti-Quality financial tool. If the investment is productive, well-planned, and generates Quality, it can overcome the cost of interest, but creating a situation where leverage is necessary due to the relinquishing of existing capital is putting the business in an anti-Quality situation. This process of decapitalization and subsequent responsive leverage is what is meant by the hyper-financialization cycle.

To de-financialize a business, saving must be an option. Until 2009, the only assets that could sufficiently hedge against inflation without substantial counter-party risk, were relatively illiquid and not suitable for a business’s treasury (i.e., high-demand real estate, fine art, gold, other company’s public stock, etc.). Fortunately, this is now possible with the invention (discovery?) of Bitcoin34. Holding Bitcoin as a treasury reserve asset will protect a business from the Quality degrading effects of inflation, while simultaneously maintaining the liquidity necessary to take advantage of market opportunities. Bitcoin does not just make saving an option, its intrinsic properties incentivize it. It is a genuine savings vehicle, and as such, it serves to lengthen the time preference of the business, prevent forced malinvestment, avoid passive capital destruction, but most importantly, it will insulate a business from the machinations of the macroeconomic environment and allow decision-makers to reclaim sovereignty of their business operations.

Furthermore, strong capitalization will allow a business to leverage its balance sheet to create even further value (at least during Bitcoin’s adoption phase). Companies on the Bitcoin standard have been able to issue convertible bonds far below market rates to finance their business operations or even simply to recapitalize5 and put themselves on a stronger foundation. Rather than being subjected to macroeconomic forces outside of their control, they are able to arbitrage the relative weaknesses of their country’s currency for the benefit of their shareholders.

In addition to intelligent (Quality) leverage, businesses are able to recapitalize by selling equity into the market and using the proceeds to purchase digital capital (Bitcoin). Selling equity is typically dilutive but can be accretive if the business does not expect to beat the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of Bitcoin with its current business operations. Additionally, inflation causes investors to seek a store-of-value which often manifests itself in asset inflation (i.e., equities). This causes business valuations to frequently be over 20x future earnings expectations (sometimes exceeding 400x). If the business believes they are benefiting from irrational asset inflation, selling equity into the market and using the proceeds to purchase Bitcoin can be accretive as well.

Quality Hurdle Rates

Integrating Quality into a business’s budgeting process through ZBB, and into its balance sheet through de-financialization, will ensure the business is on a strong foundation for making Quality decisions, but it is impossible to determine success when utilizing metrics designed specifically to measure short-term profit. For example, earnings per share (EPS), and the commonly utilized price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, assess a business’s entire value based on last quarter’s earnings.

Although not the official measure of profit using Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP) accounting, businesses also utilize “Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation, and Amortization” or “EBIDA” as a common metric for valuation. Earnings refers to the net income or profit. Depreciation and amortization refer to the reduction in value of tangible and intangible assets over time. This measurement provides an approximation of the cash flow (short-term profit) generated by the company’s operations. The consequence of utilizing this measurement is often the obfuscation of anti-Quality actions. Depreciation and amortization measure the degradation of capital assets. In order to maintain operations, these capital assets need to be maintained or replenished, so their degradation cannot be removed if the goal is to understand real profit, or Quality. Interest is the cost of capital, which is essentially a measurement of the opportunity cost of doing any other thing. If a business is interested in understanding if it is making Quality decisions, the cost of capital needs to be included. Real profit cannot be measured without keeping these key costs in the equation.

Additionally, earnings (or profitability) are typically measured using a country’s currency as a UoA. In the United States, this is the U.S. Dollar (USD). Real profit, or Quality, cannot be measured in USD, or any other inflationary currency for that matter. If using USD as your UoA, the hurdle rate should be, at a minimum, the rate of real inflation (not inflation as measured by the government). Real inflation, in this case, means the rate at which the purchasing power of the USD has decreased. Due the inequitable impact of inflation over the economy, this is a complicated measurement. Hypothetically, a business could create its own basket of goods, based on the materials and services they purchase, and measure inflation’s direct impact on their individual purchasing power, but that would not necessarily be considerate of opportunity cost. The best way to assess the impact of real inflation is to measure against something with a fixed supply (and desirable). Better yet if it is liquid so it is able to respond to the inflationary pressures in real time. Given this, Bitcoin serves as the optimal UoA, or measuring stick, and the relative purchasing power of Bitcoin should be the true hurdle rate for determining if a business has been generating Quality. This new hurdle rate can be determined by either comparing (real) profit to Bitcoin’s CAGR measured in USD, or if the business has adopted Bitcoin as its treasury reserve asset, by measuring Bitcoin Yield (i.e., the increase of Bitcoin per share on its balance sheet).

Establishing Quality hurdle rates and utilizing Quality metrics (or avoiding anti-Quality metrics) will provide a competitive advantage for a business. These Quality measurements will shift the focus from a business’s income statement to its balance sheet, determining success based on the accumulation (or destruction) of capital, rather than the existence (or lack thereof) of short-term profit. The destruction or accumulation of capital is certainly not determined by the measurements, but by measuring correctly a business can ensure decision-makers are not guessing at whether their decisions are contributing to long-term profitability. It can, and will, serve as an orienting function for decision-makers in an abstract economy.

Tripodi, T.T., “Quality in an Abstract Economy,” Thoughts on Quality

Consumer Price Index, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

Tripodi, T.T., “Bitcoin: A Protocol for Quality (Part 1 of 2),” Thoughts on Quality

Tripodi, T.T., “Bitcoin: A Protocol for Quality (Part 2 of 2),” Thoughts on Quality

Ciccomascolo, G., “MicroStrategy, Metaplanet, and MARA Embrace Debt to Buy More Bitcoin,” CCN, November 19, 2024, https://www.ccn.com/news/crypto/microstrategy-metaplanet-mara-debt-buy-bitcoin/